Strength and Power Training for Balance

Our previous blog posts on balance have focused on the 3 main balance systems as well as core strengthening. In this post, we are going to compare the differences between strength and power exercises as well as talk about what the research says about the benefits of both and how these strategies can help improve balance.

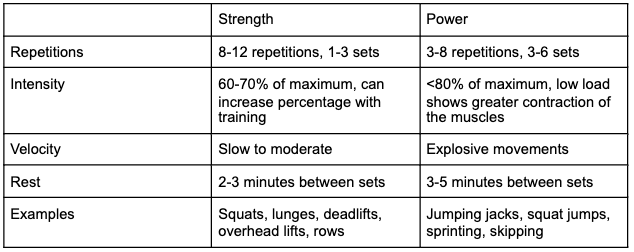

Strength training involves exercise that causes the muscles to contract against an external resistance with the goal of increasing strength, power, hypertrophy (muscle cell growth) and/or endurance. Power training is utilizing foundational strength to cause a muscle to contract against resistance in the shortest time period. Strength and power are both important concepts to understand and develop with regards to improving your balance. The American College of Sports Medicine recommends that all individuals perform strength and power training 2-3 times per week focusing on large muscle groups and functional activities. Below is a chart that compares the differences between strength and power training.

Physical therapists will use objective measures to assess a client’s balance and strength. Below are the tests that are most commonly used by PT’s. These tests are also used in many of the research studies we will talk about below. Each of these tests has normative values that indicate fall risk and give a physical therapist information on the most efficient areas to focus on in treatment.

5x sit to stand test: This test measures how long it takes to stand up and sit down from a chair 5 times without using your arms. For elderly individuals, completing the test in greater than 12 seconds indicates a fall risk and greater than 14 seconds indicates a risk for recurrent falls.

30 second chair stand test: This test measures how many times you can stand up and sit down in a chair (without using your arms) in 30 seconds. This test not only looks at your strength but also endurance.

Functional Reach: With your feet touching, put your arm out in front of you and see how far you can reach prior to needing to take a step. This test looks at your limits of stability of balance.

Timed Up and Go (TUG): Start seated in a chair, stand up and walk 10 feet forward, turn around and come back to sit down in the starting position. For most individuals, more than 13.5 seconds indicates a risk for falls.

BERG Balance: This test involves a series of 14 tasks that assess both static and dynamic balance. The total score is out of 56 points, a score of less than 40 indicates a high risk of falls.

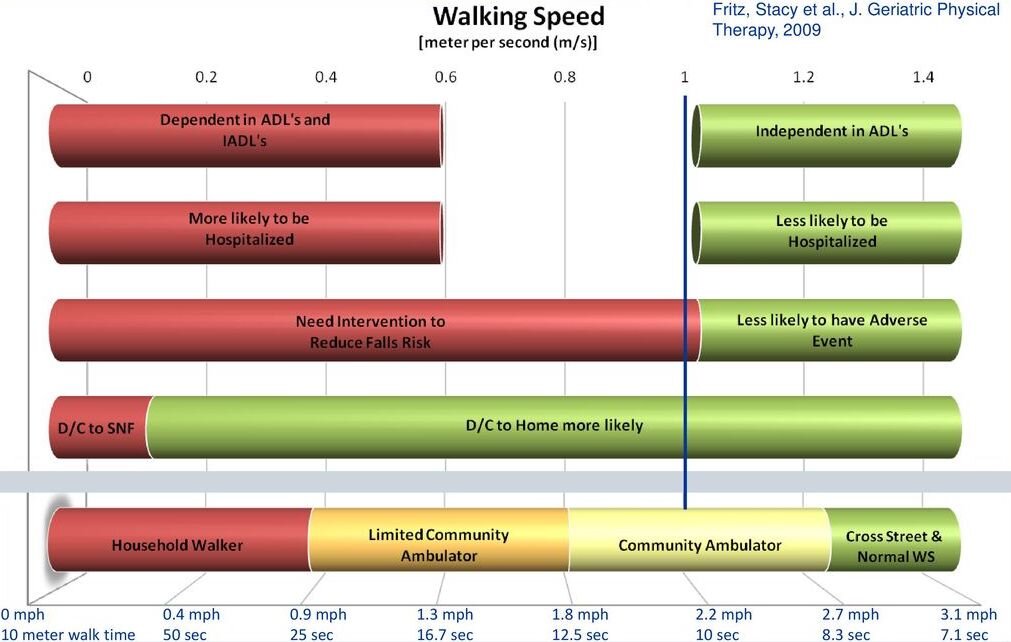

Gait Speed: This is measured by examining the speed of walking over a set distance. Gait speed is now being called the 6th vital sign due to its link with hospitalization and long term health. Check out the chart below that gives us information on what our gait speed tells us about our risk for falls.

Strength or Power?

Strength and power are both important factors in maintaining and recovering your balance. Sufficient baseline strength is necessary in order to produce adequate power for most movements. There are many research articles that look at strength and power when compared to a standard of care for therapy. Standard of care for these research studies was defined as programs that focus on balance training, stretching and breathing. Most subjects in these research studies participated in 8-12 weeks of strength or power training performed on average 3 days per week. Below we have summarized what the strongest studies have taught us about the importance of strength and power training.

Evidence for strength training:

Strength training of the calf and quadricep muscles leads to improved performance on functional reach over balance training alone.

Strength training for 8 weeks improved 30 second chair stand test results in elderly adults, demonstrating improvements in both strength and endurance.

Evidence for power training:

Power training at a low load (20% of maximum) but high speed showed greater improvements on the BERG balance assessment and single limb stance time compared to power training at medium and high loads.

High velocity training performed for 12 weeks with a weighted vest improved lower extremity strength and scores on the 5x sit to stand test by 36% in elderly women. This training program also improved gait speed and single leg stance time.

Power training that focused on explosive movements in the eccentric phase of exercise resulted in significant improvements in changing directions while turning, postural stability and recovering imbalances.

Comparing strength and power:

Power over strength training was shown to improve dynamic strength, isometric strength and gait speed.

Power and strength training equally improved maximal strength, muscle power and functional performance of the lower extremities as long as they were exercising on a moderate intensity level.

Power and strength training equally improved stepping strategy used to recover loss of balance in both the forward and side directions.

When focusing on the lateral hip muscles, power training was more effective than strength training at improving weight shifting and single limb balance.

That is a lot of data. The takeaway is this: strength AND power training are important to improve balance. A comprehensive exercise program should include BOTH strength and power exercises for maximizing overall mobility and decreasing risk of falls.

Why is strength and power so important as we age?

With each decade of life, normal aging is associated with a decrease in muscle mass and a subjective decrease in muscle function. A decrease in muscle mass is known as sarcopenia. Sarcopenia has been shown to cause a decline in not only muscle contraction, but also in strength, power and physical performance. Unfortunately as we age, a decrease in muscle mass is shown to lead to a decline in quality of life as well as an increase in fear of falling. The cycle continues and an increased fear of falling leads to decreased mobility and therefore higher incidences of morbidity and mortality.

BUT, it does not have to be this way!

If strength training is new to you, we understand! A lot of our clients tell us “I can’t lift weights, I have never tried it and I can’t move like I used to”. This may be an entirely new activity but let us assure you, strength training can be started at ANY age! Multiple research studies have looked at individuals over 70 years old who started strength training after previously having sedentary lifestyles. One very large research study included only participants over 85 years old and they demonstrated a significant decrease in fall risk with strength training in this population. Many of these studies found that strength and power training not only decreased the risk of falls but also improved self reported quality of life, increased confidence in balance and increased walking speed. The best way to start a strength training program is with a trained professional! If you are relatively healthy without significant balance impairments, going to a personal trainer is the best route to get you started on a strength training program. However, if you have balance impairments or medical conditions that may need to be closely monitored, make sure to see a physical therapist. A physical therapist will be able to use objective data (such as the tests we mentioned above) to measure functional changes in your strength. They will then be able to start you on a strength and power training program to decrease your risk of falling and increase your quality of life. If you have any questions about starting a strength and power training program, ask our team of specialized physical therapists by sending us a message to info@neurolab360.com or contact us HERE. We would love to help you!

References:

Bean J, Herman S, Kiely D, et al. Increased velocity exercise specific to task (InVEST) training: a pilot study exploring effects of leg power, balance and mobility in community-dwelling older women. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004. 52(5):799-804.

Trombetti A, Reid K, Fielding R. Age-associated declines in muscle mass, strength, power, and physical performance: impact of fear of falling and quality of life. Osteoporos Int. 2016. Feb; 27(2): 463-471.

Orr R, de Vos N, Singh N, et al. Power training improves balance in healthy older adults. Journal of Gerontology. 2006. 61A(1): 78-85.

Lopes P, Pereiera G, Lodovico A, et al. Strength and power training effects on lower limb force, functional capacity and static and dynamic balance in older female adults. Rejuvenation Research. 2016. 19(5): 385-393.

Inacio M, Creath R, Rogers M. Low-dose hip abductor-adductor power training improves neuromechanical weight-transfer control during lateral balance recovery in older adults. Clinical Biomechanics. 2018. 60: 127-134.

Bechshoft R, Malmgaard-clausen N, Gliese B, et al. Improved skeletal muscle mass and strength after heavy strength training in very old individuals. Exp Gerontol. 2017 Jun (92)96-105.

Tiggemann C, Dias C, Radaelli R. Effect of traditional resistance and power training using rated perceived exertion for enhancement of muscle strength, power and functional performance. 2016 Apr 38(2): 42.